|

|

|

This topic aims to provide background information about legislation and standardization relating to the safe design of machinery, together with the revision process of four basic technical documents, around which the ETUI-REHS has been trying to promote and coordinate a trade union focus both at national and European level. It also gives guidance on how to intervene in the production of machinery standards. In providing this information, the ETUI-REHS has benefited from the contribution of Jean-Paul Lacore and Paul Makin, two experts who have been deeply involved in the work since the birth of the machinery standardization programme back to 1985.

When the ETUC established the European Trade Union Technical Bureau for Health and Safety (now Health & Safety Department of the ETUI-REHS) at the end of 1988, one key objective was to promote a high level of health and safety in Europe in view of the drive to complete the Single Market by 1993. In 1985 the principles of the New Approach to technical harmonisation and standards were laid down by the Council Resolution of 7 May 1985 on a new approach to technical harmonization and standards (OJEC, C 136 of 4 June 1985), which moved away from the concept of directives that included detailed technical specifications. According to the Resolution, the directives adopted under Article 100A (now Article 95) of the Treaty are limited to "essential safety requirements" expressed as broad objectives, leaving supporting detailed standards to be worked out by European standard-setting bodies.

This has given greater importance to the work done by organisations like CEN and CENELEC, and has led the ETUI-REHS to coordinate and support the trade union input into European standardization work.

Since 1989, one key responsibility of ETUI-REHS has been to monitor European legislation and standardization, interfacing chiefly with the European Commission and CEN. In the context of legislation, ETUI-REHS has observer status in the Working Group of Committee 98/37/EC Machinery, chaired by the European Commission. This WG provides a discussion platform where the Commission, the Member States and the stakeholders in the Single Market discuss the practical implementation of the Machinery Directive. In the context of standardisation, as an associate member of CEN, ETUI-REHS follows two Technical Committees (TCs), CEN/TC 122 "Ergonomics" and CEN/TC 114 "Safety of Machinery".

|

| |

The Trade Union challenges

|

|

|

Why a European trade union institute dealing with technical matters?

Because the drive to complete the Single Internal Market by 1993 – stemming from the Single European Act of 1986 - affected the programme of directives concerned with health and safety at work (with two articles of the Treaty - article 100A and article 118), and was accompanied by the European Commission’s intention to ensure the free movement of goods through technical harmonisation of entire product sectors.

Standardisation comes into play

| > |

A new regulatory technique was introduced in 1985, whereby the Council's role was limited to the definition of "essential safety requirements", while the method of implementing them would be supported by standards drafted by European standards-making organisations. One of the first directives to be developed under this New Approach was the Machinery Directive.

|

The trade union reaction

| > |

In 1988 - when the growing importance of standardisation and the intention to adopt the Machinery Directive were becoming clear - the ETUC Secretariat responded by launching a study on the contribution of the two sides of industry (manufacturers and end-users) to European standardization, whose findings corroborated the need for workers' representatives to be able to influence the European harmonization of work equipment. This led to the ETUC’s decision to set up in 1989 the Trade Union Technical Bureau (TUTB), a European trade union institute specialized in health and safety matters.

|

What is currently happening at European level?

| > |

A legislative package covering the Internal Market was proposed in February 2007 by the European Commission aimed at fostering intra-Community trade in industrial goods. Trade unions are concerned about whether such horizontal cross-sectoral policy initiatives might affect the health and safety of workers. One area of trade union concern is the current consolidation of the New Approach Regulations/Directives as an ongoing work in line with the simplification of the regulatory environment in the context of better regulation policy. One issue of concern here is the balance between EC harmonisation of national technical rules and "mutual recognition". Another important aspect is the role of the different internal market operators in the context of certification and market surveillance.

The ETUI-REHS wonders what the impact of such horizontal cross-sectoral policy initiatives will be on very different business sectors. Secondly, standardisation will increasingly support EU policies, according to the European Commission: e.g., the approaches formulated in the most recent Action Plan for European standardization, and the vision developed by the Commission discussion group EnginEurope for the European Mechanical Engineering industry.

|

Why has standardisation become important to trade unions?

In the context of equipment used at work, European standards-making bodies were assigned the task of formulating the design specifications that meet the health and safety objectives of the Machinery Directive. Therefore, low quality standards might result in a negative health and safety impact on workers.

The background to machinery regulation

| > |

Under the New Approach to technical harmonization and standardization, the public authorities lay down the "essential health and safety requirements (EHSRs)"- expressed as broad objectives – that machinery placed on the Community market must meet if it is to benefit from free movement within the Community.

|

| > |

The detailed technical specifications of machinery that meets these objectives are laid down in voluntary ‘harmonized’ European standards adopted by CEN or CENELEC under an official remit (the "mandate") to give practical effect to the EHSRs.

|

| > |

Machinery manufactured in compliance with these harmonised standards benefits from a presumption of conformity with the applicable essential requirements.

|

Key points for trade unions

| > |

Standards developed by private bodies are becoming an essential ingredient of protective and preventive legislative requirements: important issues for the health and safety of workers are negotiated outside the workplace.

|

| > |

Trade unions now face the challenge of maintaining the ability to influence the regulatory mechanism covering technology at work which they had before, when they were consulted on regulations being adopted at national level.

|

| > |

The shift from the national fragmented discussions on technical matters among different Member States that have now been centralized in the context of total harmonisation: one European standard all across Europe.

|

| > |

Standardisation has the potential to provide the platform for collaborative work between engineers, employers, workers, manufacturers, researchers and governments who can contribute to better health and safety through consideration of design issues.

|

| > |

Through standardisation in particular, trade unions can explore pathways to deliver the aim of putting workers' knowledge to best use in improving the working environment. The focus will be on what information can be extracted from the working environment to help improve the design of work equipment.

Machinery standardisation under the New Approach deals with design, and design is contributory in a significant proportion of workplace deaths and injuries involving machinery. This explains why trade unions must work for a better quality of these 'harmonised' design standards supporting the Machinery Directive.

|

How does the system work in practice?

Standardisation is a combination of work at national and European level, which requires action by national trade unions complemented by European networking and coordination.

The basics of technical standardisation

| > |

Harmonised standards for machinery are European standards, adopted by CEN or CENELEC, following an official request - a ‘mandate’ issued by the European Commission after consulting Member States - to interpret the EHSRs of the Machinery Directive;

|

| > |

CEN and CENELEC are essentially assemblies of national standardisation bodies (NSB): standards emerge from the coordinated work of technical committees (TCs) and working groups (WGs) made up of delegates appointed by the NSBs;

|

| > |

Draft versions of these standards are made available at national level for public comment before approval;

|

| > |

Before being adopted, standards are put to the vote by NSBs: there is one vote per NSB (therefore, per country), whereas at national level there will be different interests with different priorities (manufacturers, users, trade unions, and governments);

|

| > |

Confidential technical assessments addressed to the standard-setters are carried out by consultants in charge of checking the compliance of draft standards with the mandates issued by the European Commission;

|

| > |

Member States may object to draft standards that are thought not to deliver the EHSRs, and a safeguard clause exists to address failings identified at a later stage;

|

| > |

The European legislature plays its role, as the references of these standards must be published in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJ) for them to have legal effect (presumption of conformity);

|

| > |

Finally, a policy for the revision of standards is in place to maintain their quality over time;

|

| > |

For many machinery harmonised standards the revision will coincide with the adoption of a single standard at European (CEN) and international (ISO) level, using the procedures of the Vienna Agreement co-operation between CEN and ISO.

|

Key implications for trade unions

| > |

What does "consensus" mean in the European standardisation model? Does the "national consensus" brought into the CEN system reflects a "balanced" representation of all interests concerned in the standardisation process? As each national standardisation organisation can only take a uniform national position in the voting, societal stakeholders will strive to exercise their influence through the national standardisation work and as members of the national "mirror" committees.

|

| > |

Therefore, trade unions need to take every opportunity to participate in national delegations in order to influence the consensus and raise national delegates’ awareness of health and safety at work matters.

|

| > |

Maximum benefit will be achieved when trade unions influence more national delegates, in order to inject health and safety concerns into a whole TC or WG. This means collaborating with trade unions in other Member States and achieving a common trade union view under the coordination of ETUI-REHS.

|

| > |

The passage of safety standards from CEN to ISO and back adds new features and brings new challenges for trade unions: the relation of standards to legislation, the duties of manufacturers and users, the framework in which standards are prepared, the representation of legitimate workers' interests.

A combination of trade union pressure into NSBs and European-level coordination through ETUI-REHS can help ensure that acceptable standards emerge from CEN/CENELEC work. When moving from CEN to ISO, for European trade unions this shift significantly adds to the costs and so steadily reduces their involvement. Trade unions need to counterbalance the limitations of the consensus achieved in standardisation, where manufacturers are proactive to achieve the economic benefits gained by imposing technical solutions that reflect their know-how. On the other hand, trade unions play in an area where safety has been historically considered as in competition with productivity.

|

What can trade unions bring to standardisation and how?

Trade unions can be a key vehicle for informing standards with workers' shop floor experience, demands and expectations. In the context of machinery safety, the use of feedback from operators into standardisation ensures that standards are more human-centred, and take into account the human-machine interface in the whole range of conditions of use.

The legislative framework

| > |

According to Article 5 of the present Machinery Directive 98/37/EC (Article 7 of Directive 2006/42/EC which will need to be applied from 29 December 2009), Member States shall ensure that appropriate measures are taken to enable the social partners to have an influence at national level on the process of preparing and monitoring the harmonised standards. Over the years the measures taken by Member States have been very diverse. In some, institutional structures (like the German KAN) provide support, in others formalised procedures exist to facilitate trade union participation, while yet others have specific provision in place. Many Member States do not provide any support for trade union participation. A stock-taking analysis is missing. According to the European Commission Action Plan for European Standardisation, a recommendation for action addresses the promotion of effective participation by all interested parties, and invites Member States to report on state of play of the implementation at national level of the measures taken to enhance the participation of stakeholders at European/international standardisation.

|

Key lines of action for trade unions

| > |

ETUI-REHS’ work on standardisation started by focusing on the horizontal fundamental safety standards (called "A" and "B" standards) drafted by CEN technical committees TC 114 and TC 122, with the aim of introducing health and safety concepts of trade union concern. Over the years, attention has turned towards specific vertical standards covering types of machine (called "C" standards). ETUI-REHS now wants to take stock of CEN’s technical work on machinery, and look at what impact A & B standards have had on the C-type standards.

|

| > |

At the same time, ETUI-REHS is developing a project whereby shop floor feedback on specific equipment is brought up to the standards setters who are drafting the specifications of that equipment. This worker knowledge is collected through a methodology, and complements manufacturers' know-how. The challenge for the future will be how to consolidate the top-down (influence on A & B standards by injecting health and safety at work concepts) and bottom-up (influence on technical specifications by feedback of shop floor experience) trade union approach.

|

| > |

Finally, ETUI-REHS aims to “go beyond” design: take the example of the interface between the risk assessment carried out by manufacturers, and the risk assessment carried out by employers integrating machinery in a specific working environment. Here the keyword is "interface": ETUI-REHS helps trade unions work with other experts in order to create a culture able to deal with such interfaces. The next step is to bring together the bottom-up and top-down knowledge flow, where safety and design condense in a safe by design culture.

|

| > |

Another essential element under trade union scrutiny is the accumulation of knowledge, where machinery evolves with innovation and technological developments; this involves maintenance of standards in a more open public debate.

|

| > |

Design of machinery is based on approximately 600 design specifications drafted by the European standards-making organisations CEN and CENELEC: trade unions need to set priorities before taking action.

|

| > |

The priorities will depend on a number of parameters, like the impact of the standards on the final design of machinery, the significance of the user interface, and the risk level associated with that interface.

|

| > |

Technical knowledge alone provides only a partial solution to taking real work needs into account. It needs to be supplemented by the input of ergonomic analyses of real work situations.

|

| > |

As governments leave it to standardisation to regulate public interests, they are responsible for the participation of public sphere representatives in standardisation. By the same token, as governments leave it to CEN and CENELEC to interpret the Machinery Directive, facilitate trade, and set the state of the art directly affecting workers health and safety, they are responsible for participation by workers' representatives in standardisation. Standards must be informed by the lessons learned from the use of machinery designed according to them.

In a nutshell the ETUI-REHS’ expectations are:

| 1. |

A series of health and safety principles must be entrenched in horizontal standards;

|

| 2. |

A bottom-up strategy must be put to work, where a new method of working builds up knowledge that integrates the experience of workers and prevention practitioners;

|

| 3. |

Technological innovation must be reflected in standards in a timely and efficient manner; Consensus alone is not enough.

|

|

|

| |

Machinery standardisation

|

|

|

The work of CEN and CENELEC in the context of the New approach

CEN and CENELEC are the European Standards organizations mandated by the Commission to produce harmonized standards in support of New Approach Directives. Most, if not all, New Approach Directives have their own programme of standards and each directive depends on a separate mandate defining what is required. Some Directives are covered by mandates for both CEN and CENELEC and some are specific to one or other of the organizations.

Following a mandate issued by the European Commission after consultation of Member States, harmonised standards are developed and adopted by CEN or CENELEC, through their Technical Committees (TCs).

| The legal relevance of harmonised standards |

|

Application of harmonised standards remains voluntary; however, machinery manufactured in accordance with a harmonised standard whose reference has been published in the Official Journal of the European Union shall be presumed to comply with the essential health and safety requirements it covers. Even if a manufacturer chooses not to apply the specifications of the relevant harmonised standard, he cannot ignore it. The manufacturer can choose alternative technical solutions, but, since he must take account of the state of the art, he must achieve a level of safety at least equivalent to that represented by the specifications of the harmonised standard.

|

CEN and CENELEC TCs draw their membership from the National Standards Bodies (NSB) of each country and it is these NSBs that manage the work of CEN and CENELEC. The Secretariat – and usually the Chairman – is provided by one NSB. There is normally a "shadow TC" in each NSB and input into the CEN / CENELEC TCs is via the shadow TC. In some countries, separate organisations represent CEN and CENELEC. Individual standards are usually produced by separate Working Groups (WGs) made up of technical experts nominated by each national "shadow TC". The WGs are managed by the CEN/CENELEC TC. This simplified scheme displays the European and national dimensions of the CEN.

CEN and CENELEC elaborate harmonised standards through an open and transparent process, built on consensus between all interested parties.

The elaboration of a European Standard includes a public inquiry, followed by an approval by weighted vote of CEN/CENELEC national members and then final ratification. When draft standards are distributed to the national members for public comment (this procedure is called the "CEN/CENELEC enquiry"), the ETUI-REHS may submit its opinion. This simplified scheme displays the standards development process in CEN, which will be described in detail in the section "ETUI-REHS action: improving principles and building up knowledge".

The ETUI-REHS interacting with CEN

The ETUC set up the TUTB (now Health & Safety Department of the ETUI-REHS) in 1988 to provide support for trade union representatives working in the field of health and safety at the workplace, and in particular those involved in the work of technical harmonization at Community level and in European standardization bodies.

The Health and Safety Department of the ETUI-REHS is an associate member of the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) since 1993. It keeps close track of the development of the technical standards mandated by the European Commission. As an associate member of CEN, the ETUI-REHS follows the activity of two Technical Committees:

| > |

CEN/TC 122 "Ergonomics" and

|

| > |

CEN/TC 114 "Safety of Machinery", whose main activity is standardisation of general principles for safety of machinery, incorporating terminology and methodology.

|

The ETUI-REHS is a partner of the Safety of Machinery Sector Network. We follow its activity in particular by attending the meetings of the so-called Advisory Nucleus group, consisting of the Rapporteur together with a balanced representation from the community of sectoral partners. The Rapporteur represents CEN at meetings of the Working Group of Committee 98/37/EC concerning Machinery, chaired by the European Commission. It is there that the Rapporteur provides updates on the activities of the CEN Safety of Machinery Sector.

The development of the programme of standards in support of the Machinery Directive: how CEN TC 114 works

The CEN machinery safety programme is carried out by over 40 Technical Committees setting out standards containing technical specifications meeting the requirements of the Machinery Directive. CENELEC is also responsible for a significant number of standards particularly in the areas of electrical safety and hand-held portable machines.

The CEN website provides a portal providing basic information on the "umbrella" Technical Committee TC 114. It includes the executive summary which explains the business environment, the expected benefits and the priorities of this committee. It also provides access to the list of standards under development and the list of standards already published by CEN/TC 114.

When CEN was given the initial mandate to produce standards in support of the Machinery Directive, TC 114 was formed with the task of writing the initial standards. It met for the first time in June 1985 and formed three Working Groups (WGs) to produce:

| > |

EN 292:1991 (parts 1 and 2) Safety of machinery - Basic concepts; general principles for design

|

| > |

EN 294:1992 Safety of machinery - Safety distances to prevent danger zones from being reached by the upper limbs

|

| > |

EN 1070:1993 Safety of machinery - Terminology

|

EN 292 was intended to give strategic guidance in the application of EHSRs listed in Annex I of the Machinery Directive. Work on developing the Directive and these standards continued in parallel until the Directive was completed in 1989.

However, it soon became clear to the national experts working at CEN that there was going to be the need for many standards dealing with individual machines or classes of machines. There was a real possibility that each WG would deal with basic requirements on, e.g., guards, safety devices and control systems in a slightly different way. In other words, there would be duplication of effort and much waste of time and scarce resource. The experts decided that the machinery standards should be managed as a coherent programme and organised the set of standards in the following way:

| A-standards |

These standards would apply to all machines and give the strategic approach to Annex I of the Machinery Directive (e.g. EN 292 Basic concepts; general principles for design, EN 1050 Principles for risk assessment and EN 60204-1 Electrical equipment of machines).

|

| B-standards |

These standards would deal with safety devices and techniques that could be applied to all machines where relevant. Approximately 120 B-standards have been developed.

|

| C-standards |

These standards would deal with specific machines or groups of machines and would provide a presumption of conformity with the EHSRs covered by the standard. Approximately 700 C-standards have been developed.

|

The logic was that the writers of the C-standards would use the A-standards and draw on the relevant B-standards when writing their standards. By then end of 1990 the programme contained some 120 standards. However, it became clear that whilst the need for standards had attracted a lot of support from all of the stakeholders, much of the work was uncoordinated and did not meet the requirements of the Machinery Directive. There was the need to give the TCs and WGs some precise guidance on how they were to execute their work. Two things were done to help. The first was to appoint the first CEN Consultant for Machinery Safety. The second was to produce EN 414 Rules for the drafting of Machinery Safety Standards. This is an integral part of the machinery programme but it is not a Harmonised Standard – it is an essential guide for writers of standards.

Information on the mandated standards programme “Directive 98/37/EC - Safety of Machinery” is regularly provided to the Commission by the Rapporteur of the machinery safety sector, and made available in the CIRCA website, accessible to all stakeholders.

Writing standards: an articulation of methodology and knowledge

Whilst much important information and guidance can be obtained from the B-standards, it is important to understand that, to write a successful C-standard, the WG requires experts able to contribute the following information:

| > |

how to write a harmonised standard – i.e. how to follow the principles of EN 292 and EN 414;

|

| > |

how the relevant machine is designed;

|

| > |

how the machine is used;

|

| > |

the accident history for the machine or similar machines;

|

| > |

knowledge of inherently safe design principles, of the available safety devices and how to use them.

|

This means that the WG must have access to expert opinion from safety professionals, manufacturers and designers, consumer groups, corporate users and Trade Unions.

Against this background stands the ETUI-REHS strategy aimed at 1) injecting health and safety principles into 'horizontal' machinery standards, and 2) developing tools to accumulate workers knowledge and feed back it into harmonised standards.

ETUI-REHS strategy in action: improving principles and building up knowledge

1. The work to improve horizontal machinery standards

In the context of the CEN machinery safety programme the ETUI-REHS has been monitoring the revision of four fundamental European safety standards: EN 292, EN 1050, EN 954, EN 414. As these standards lay down basic safety concepts and procedures to be used across a wide range of work equipment, their revision has provided the ETUI-REHS with valuable insights into the complex process of reaching a European and international consensus on core principles of machinery safety in an increasingly global market.

2. The ETUI-REHS network of experts on standardisation

The participation of ETUI-REHS in the various bodies where standards are drawn up is based on a network of trade union experts, with the aim of improving the conditions of European workers. These contributions are especially rooted in the experience of workers as the end users of products, equipment and installations and in the experience of workers' representatives in establishing and putting into practice a prevention policy at enterprise, sectoral and member state levels. The annual meeting of the European network of trade union experts on standardisation is the most important opportunity to transfer trade union knowledge from the national confederations to ETUI-REHS, in order to shape its annual strategy to improve trade union influence on standardisation.

Since it was set up in 1990, the ETUI-REHS network of experts in standardisation has passed through several different stages in its functioning, and its work priorities, defined jointly with the HESA Department, have evolved significantly. The meeting held in Prague in 2005 represented significant progress in the way the network will operate in the years to come. ETUI-REHS has revised the functioning of its standardisation network in two ways. Firstly, meetings will from now on be organised in different member states to better alert trade unions to standardisation, and to better collect national trade union needs and experiences. Secondly, meetings will include an "open session" where guest experts will help trade unions put into practice the OHS strategies elaborated within the network.

3. How Trade Union can influence the standard making process in CEN and CENELEC

Introduction

From the standpoint of an individual TU Member the whole process of producing a Harmonised Standard in Support of the Machinery Directive looks very remote and complicated. Regrettably, the whole procedure still seems to be dominated by large organisations with the huge resources need to send delegates to all of the meetings. However, it is still possible for an individual or a small organisation to have their say in the process and perhaps make significant changes to the work. This section describes the key stages of the standards making procedure and how and when to make a successful input.

Preparation

A famous and successful general once said that time spent in preparation and planning in never wasted and the same is true for making an impact in the preparation of a standard. Trade unions need to know who the other participants are, what part they will play and how they are likely to influence the eventual outcome. They also need to know about each key stage (KS) of the standards making process and how to intervene and make their views known.

Why would trade unions want to make an input?

They may: </ TBODY>

| > |

Want a new standard prepared for a machine they have a particular interest in

|

| > |

Get an existing standards revised

|

| > |

Comment on a standard already in the preparation

|

| > |

Complain about gaps in an existing standard

|

| > |

Prevent a standard that has passed the formal vote (FV) from being published in the Official Journal of the European Union as a Harmonized Standard

|

| > |

Ask for a standard to be withdrawn from the list of Harmonized standards.

|

Getting to know the participants

Making a European Harmonized Standard consists of a series of formal steps designed to make the process transparent and to allow all the stakeholders to have an input into the process. Many organisations at both the national and European level will want to take part. Traditionally, the main players have been the manufacturers of the machine in question with perhaps large users, insurance groups and national labour inspectors adding to the work.

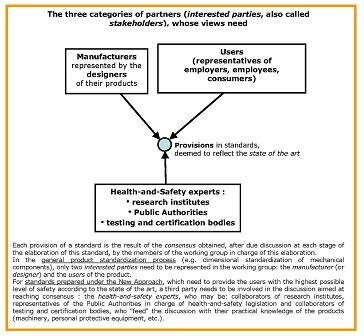

However, with the advent of Harmonized Standards in support of New Approach Directives the European Commission made it clear that the standards should be produced with contributions from all the stakeholders, including, manufacturers, users, Trades Unions, insurance organisations, third parties inspection bodies and labour inspectors (representing Member States).

At national level this means that there may be twenty or more groups who may contribute to individual standards. Each one of these organisations is potentially an ally who will help Trade Unions to input information into the standard. It is important to remember that making a harmonized Standard is essentially one of consensus building between stakeholders within the legal framework of the Machinery Directive and Trade Unions have every right to be part of that process.

Trade Unions don’t need to be shy about making a contribution. In many, ways they are best placed to know about a machine and they could have essential information not available to the other stakeholders.

But how do Trade Unions make a start?

Finding out who is involved

Trade Unions need to know who is taking part and who could be a likely friend to help you make an input. The Internet is a valuable tool in this process, as most stakeholders will have their own website. The list of contacts is a long one and one may not need to use all of the steps but it is essential to know what is there.

Step one - is to ask your Union if they are involved and, if the answer is yes, make contact with that person. They should know who else is interested at your national level. It may be that there is an ETUI-REHS expert in standardisation in the organisation and this will be like striking gold.

Step two - Find out if there is a Technical Committee in your national standards organisation – see the membership page on CEN and CENELEC websites. If there is a TC working on the relevant machines obtain the name and address of the TC Secretary.

Step three - Ask the national TC Secretary for a list of members and their organisations. This will enable you to see who is involved and who could be useful in forwarding your interests. Ask for details of the relevant CEN or CENELEC TC preparing the standard and who goes to the TC meetings.

Step four - Go to the CEN or CENELEC website and get the details of the relevant TC. Get the name of the Secretary and Chairman. Check the work programme to see if they are working on the standard you are interested in. See if there is a published standard.

Step five - If there is work in progress ask the TC Secretary for the name and address of the relevant Working Group (WG) Convenor. Make contact and ask for the names of the technical experts in the WG. See if there are any useful contacts.

Step six - Find out the name(s) of the CEN/CENELEC Consultant(s). Formally, you are not supposed to approach the Consultant(s) but there is nothing to prevent you making your views known. You could make a vital contribution to resolving a difficult problem.

Step seven - Find out which government department deals with machinery safety and the name of the person who is responsible for overseeing the standards programme (usually a labour inspector). They may well be contributing to the WG. Equally importantly they will make a contribution to the Commission 98/37/EC Working Group that deals with problems arising from the implementation of the Machinery Directive. This includes commenting on Harmonized standards which have been challenged for no-compliance with the ESRs.

4. Key stages (KS) in the development of a Harmonized standard

The previous section showed how to identify persons in the standards making process who could be useful in putting forward Trade Union views. This section shows how and when to intervene in the process.

European standardization is designed to be transparent so that all stakeholders to take part in the process. The procedure from initiation of a new work item to the publication of the finished standard follows a formal procedure that is a series of clearly defined key stages (KS). The price for all this transparency is that the whole process can take a long time. The advantage is that all stakeholders have the opportunity to take part in the process – if only by making comments to their National Standards Body (NSB).

In addition, for Harmonized Standards, Member States have the legal right to challenge the publication of a new or existing standard in the Official Journal of the European Union for not meeting the requirements of the Directive. Every person within the EU has the democratic right to make their views known to their national government.

Trade Unions do not necessarily have to take part in the whole process if they do not want to. The skill in getting their views known is choosing the appropriate key stage. If Trade Unions need help the ETUI-REHS will be able to help Trade Unions choose the correct approach.

The following are the key stages (KS) in the standards making process where and when Trade Unions can make their views known:

KS 1 - New work item (NWI) - Every standard starts as a NWI. A proposal for a new standard usually comes from the shadow TC in the national standards organisation – although it can come from the CEN/CENELEC TC secretariat. Proposals can be made by anybody with an interest in the relevant machine. It stands more chance of success if it is accompanied by a draft standard – or at least a very clear description of the standard is intended to cover.

KS 2 - Revision to an existing standard - A similar process to a NWI. NB. Existing standards come up for review every five years. This will appear in the CEN/CENELEC TCs work programme as a NWI.

KS 3 - Adoption by the CEN/CENELEC TC as a NWI - The NWI is adopted by the national TC and put to the CEN/CENELEC TC to be voted on for inclusion in their work programme and given a CEN/CENELEC number. At the same time a convenor is appointed to lead the WG. NB. The same stages are used if the standard is to be written in an ISO WG under the parallel procedure. In addition, a Consultant is appointed to oversee the standard.

KS 4 - Potential Harmonized Standard - The NWI is adopted by CEN/CENELEC and the Commission as a standard in support of the Machinery Directive.

KS 5 - Starting work - The CEN/CENELEC TC sets up a WG and the appointed Convenor calls for experts from the national standards bodies to join the WG.

KS 6 - Producing the draft standard - The WG meets and produces what they consider to be a complete document. This may take over a year and involve several meetings. It is anticipated that the individual experts will consult their shadow national WG and feed back their comments into the work. When the work is finished the draft standard is sent back to the CEN/CENELEC TC.

KS 7 - CEN/CENELEC Enquiry - The CEN/CENELEC TC meets and agrees that the draft Standard can go to the 6 month Enquiry. The TC Secretariat send the draft standard to each national standards body so that all identified stakeholders can comment on its suitability as a standard and make details comments on its contents.

KS 8 - Examination by the Consultant - The standard is examined by the appointed Consultant who makes a detailed report on the compliance of the standard with the Directive. The report is sent to the WG.

KS 9 - Comments resolution - At the end of the Enquiry the comments received are collated (including the Consultants report) and go to the WG for the “comments resolution” meeting(s). A final draft is produced and sent to the TC. Only comments resulting form the Enquiry are considered and either accepted or rejected. A record is kept of this procedure.

KS 10 - Pre-Formal Vote - The TC agrees that the draft standard should go to the Formal Vote and sends the final version to the Consultant for comment. If the Consultant makes adverse comments these have to be resolved with the TC before the standard can proceed any further.

KS 11 - Formal Vote - The CEN/CENELEC Central Secretariat (CS) sends the standard to NSB for the six month Formal Vote. The vote is yes or no and the NSB consults widely before making a decsion.

KS 12 - Post Formal Vote - If the vote is successful it is sent back to the TC for editing. If the vote is unsuccessful it is sent back to thee TC with the adverse comment to see if modifications can be made without altering the technical content of the standard. When the standard passes its FV, NSB have the opportunity of registering a Formal Objection to the publication of the standard if there are serious objections on health and safety grounds. If the objection is upheld the standard is sent back to the TC for modification and a second FV. The finished standard is ratified by CEN/CENELEC C/S and sent to Member Bodies for translation and publication.

KS 13 - Publication in the OJ - At the same time the standard is sent to the Commission for publication in the Official Journal of the European Union as a Harmonized Standard.

KS 14 - 98/37/EC Scrutiny - The Commission Machinery Directives Group 98/37/EC made up of representatives from Member States (MS) plus observers from interested organisations such as CEN/CENELEC may scrutinise the standard if a MS has indicated concern over its contents. It may ask for the FV to be postponed and sent back to the TC or ask for a published standard to be removed from the Official Journal of the European Union and modified.

|

Once published any Member State can object to the standard being in the Official Journal because of on compliance with the Directive and ask for the standard to be scrutinised by the XXX Committee. In practice the standard is referred to the 98/37/EC WG for a technical examination and recommendations. This may lead to the standard being removed from the Official Journal. Recommendations are passed back to CEN/CENELEC with a request to modify the standard. In practice this will mean a revision to the standard.

|

5. The strategy for improving machinery standards through users' feedback

Based on their experience and practical knowledge of the equipment, users constitute a precious source of information on the adaptability of the technical solutions provide by the manufacturer. Exchanges of information between manufacturers and users may help to improve the design of equipment, in particular by revealing certain unusual uses of machines by their operators.

This feedback also seems essential with regard to harmonized European standardisation aimed at ensuring that the proposed design specifications are geared to the working conditions in companies. Developing standards is a long process that often takes several years before their publication. As a result, some standards may mention solutions which have since been superseded by recent technological advances, even if these standards may be revised every five years. Moreover, some machines are still not covered by harmonized European standards; for standardisation bodies have not yet been able to tackle all the areas covered by the EU directive on machine design. This machinery directive envisages participation by machine users. However – as confirmed by the TUTB study on the application of this text in Germany, France, Italy and Finland – few workforce representatives influence this process in practice.

Nonetheless, we are convinced of the importance of the various players in the system exchanging information and experiences. Manufacturers and users have a different approach to their machines and also use a different language: while the former use a highly technical vocabulary and are bound by economic constraints and productivity, the latter have a practical approach to the matter - they may not be familiar with EU regulations, but they are aware of the difficulties involved in using the equipment. We will have to ask ourselves how we can facilitate the dialogue between these two actors.

Feedback in action

Following a data collecting project run in co-operation with the Swedish Union LO in 1997, the ETUI-REHS in 1998 commissioned SindNova, an Italian trade union institute, to develop a research project to involve workers and firms in assessing the effectiveness of technical standards on the safety of woodworking machinery. The project was carried out in 1999 in Tuscany, Italy, by Fabio Strambi and colleagues from the Siena Local Occupational Health & Safety Unit (USL). It aimed to introduce a participatory model in a specific high risk industrial environment, collecting input from machinery users and integrating it into a strategy for improving machinery technical standards. The outcomes were published under the title: Ergonomics and technical standards: users’ experiences and suggestions - Safety of woodworking machinery.

In 2003 the Bilbao Agency awarded the "Feedback Methodology" in the context of the SME Funding Scheme 2003-2004, when Italy (Regione Toscana) and Germany (GrolaBG) decided to apply this methodology to forklift trucks (FLTs). This project was carried out in 29 SMEs where a total of 192 forklift trucks were used.

The project outcomes were then used to develop a wider European project across five member states, centred on FLTs covered by the harmonized standard EN 1726-1:1999 Safety of industrial trucks - Self-propelled trucks up to and including 10 000 kg capacity and industrial tractors with a drawbar pull up to and including 20 000 N - Part 1: General requirements.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The Machinery Directive – one of the first New Approach Directives

The Machinery Directive was one of the first New Approach Directives to be developed by the Commission and subsequently Member States. Its purpose was to remove barriers to trade caused by different requirements for machinery safety promulgated by Member States.

Work started in 1984 with the Commission producing a draft directive based on a combination of regulations from Member States – the normal practice for preparing directives. However, significant problems occurred because national regulations prescribed specific technical requirements for a given machine and these were all different in some aspect. Moreover, this approach did not include all machines – particularly robots and other computer-controlled machines – and many hazards, such as noise, vibration, toxic materials and ergonomic aspects. Therefore a risk-based approach to basic machinery hazards was adopted and these were expressed as a list of essential health and safety requirements (EHSRs) that make up Annex I of the directive.

The directive places on manufacturers administrative and technical obligations that must be met before machines can be placed on the market. It regulates a wide range of industrial sectors handled by the Directorate General for Enterprise & Industry of the European Commission.

The interplay between Law and Standards

The EHSRs represent the objectives to be achieved, while the detailed technical specifications for attaining these objectives for each product type are dealt with in harmonised European standards adopted by CEN or CENELEC on the basis of consensus between interested parties. According to the Machinery Directive, application of the essential requirements must take into consideration both a risk assessment for the type of machine concerned and the “state of the art”. Under the New Approach, the job of reflecting the “state of the art” for a particular aspect of machinery safety or for a particular type of machine is assigned to technical standards. The machinery standards programme is dealt with in the section "The European system of harmonized standards for machinery safety".

The European approach to safe machinery design

1. The risk-based approach

When the work on the machinery directive started, H&S experts from some Member States recommended that the traditional approach in drafting technical regulation should be abandoned and the Directive should be based on identified hazards, the assessment of risks and the elimination or reduction of risks arising from the hazards. This approach had the advantage of allowing any combination of hazards and risks to be dealt with across the complete range of machines – it allowed total flexibility. It also gave the prospect of the Directive being ready by 1992. Member States adopted the risk-based approach at the beginning of 1985 and this was incorporated in Annex I as the list of Essential Health and Safety Requirements (EHSRs).

The Machinery Directive was the first New Approach Directive to use Risk Assessment as a means of dealing with the hazards covered by the Directive. This approach proved so successful that all subsequent directives adopted a similar approach – as did the tranche of Directives dealing with labour protection produced at the same time.

| Risk assessment |

Risk Assessment is a very powerful tool that enables any risk or combination of risks arising from the use of machines to be eliminated or minimised according to the state of the art. The fundamental approach is stated in Annex I, Section 1.1, Principles of safety integration, of the Machinery Directive and given in more detail in EN ISO 12100 Safety of machinery — Basic concepts, general principles for design and EN ISO 14121 Safety of machinery — Principles of risk assessment.

There is still a lot of confusion between “hazard” and “risk”. The two terms are regularly interchanged and this causes confusion and misunderstanding. It is therefore useful to start any discussion on risk assessment with some basic definitions taken from EN 12100-1:2003:

Harm: physical injury or damage to health

Hazard: potential source of harm

Risk: combination of the probability of occurrence of harm and the severity of that harm

Risk assessment: overall process comprising a risk analysis and a risk evaluation.

The identification of the hazards associated with the use of a machine is a factual exercise that can be achieved by a careful study of the machine. The next step is to consider each hazard and assess what risks arise from the machine at each stage of the machine's life cycle – not just the productive phase. The risk assessment then moves on to evaluate what risks require action and what that action is. This part of the process is the most difficult and little understood.

It must be made very clear that assessing the action level for each risk and or combination of risks requires one or more persons to exercise considerable judgement over what is required. This judgement cannot be exercised in isolation and requires the following basis knowledge and inputs:

– knowledge of how the machine is designed and used;

– knowledge of accidents associated with the same or similar types of machine;

– knowledge of the available risk reduction techniques and devices;

– knowledge of the relevant safety regulations.

|

It is unlikely that all of the knowledge needed to carry out risk assessment is contained in one head. Therefore the exercise will require several individual inputs. The New Approach put the task of writing harmonised standards in the hands of the European standards organisations because the Working Groups would contain Europe's best experts who have all of this knowledge. But the importance of risk assessment goes well beyond its use by standard-setters. In fact, where machinery standards do not exist and where it is necessary to check a machine, there is no reason why the correct group of experts could not carry out a successful risk assessment using the same principles. The next section provides a closer look at them.

2. Basic principle and methods

At the advent of the European single market on 1 January 1992, thanks to the Machinery Directive, EN 292 and its first "satellites", Europe had a body of regulations and standards based on sound, and, for the most part, tried and tested design principles and methods:

| A |

the safety integration principle, enshrined by Annex 1 of the Machinery Directive: safety must be integrated to the greatest extent possible at the design stage, i.e., the designer must eliminate or reduce as far as possible the risk resulting from every hazard generated by the machine;

|

| B |

an iterative method (by successive "loops") of risk reduction at the design stage; in this method, design-integrated safety measures are applied at each “loop” as the result of an initial assessment of the risk, and their effect is assessed not just by reference to the reduction of risk achieved, but also by reference to considerations such as not generating new hazards, whether the machine retains its ability to perform its function, whether the operator's and other parties working conditions are unimpaired (concept of adequate risk reduction);

|

| C |

the “3-step method”, by which the designer will make the best possible use of, successively, inherent design measures, then safeguarding measures, and finally information for use.

|

The safety integration principle

A designer of machinery, who takes every possible step to ensure that to work safely, all a user need do is to stay within the limits of normal use, is applying safety integration.

This might seem so obvious as not to be worth mentioning. But it has not always been that way. Where mechanical hazards, at least, are concerned, early-to-mid-20th century machinery catalogue pictures show that users still had to add on many safety devices so as not to expose machinery operators to immense risk.

Arguably, machinery operators’ employers and trade union representatives, backed up by safety inspectors (labour inspectors and prevention agency staff) and armed with work accident and work-related illness figures, were able to step up the pressure on manufacturers to design safety into their machinery.

But it was not until the latter half of the century that a sufficient head of pressure built up to push the idea of safety integration effectively, and eventually win legislative recognition and backing for it.

It was clearly an idea whose time had also come in all European countries, since the partners engaged in framing the Machinery Directive apparently had no difficulty laying down the rules of sound safety integration when framing it.

Likewise, the members of the CEN Technical Committee 114 had excellent benchmark documents – plus properly briefed experts – from a wide range of sources across Europe to work out the initial draft of EN 292 in 1985.

The concept of adequate risk reduction

Designers - as all decision-takers - have to find a balance between sometime conflicting demands when facing the question "how safe is safe enough". EN 292:1991 stressed that the designer must aim to avoid – or, if that is not possible, reduce – risks, to a level where safety is adequate, i.e. reducing the risk as much as he can in ways which do not adversely affect other aspects of use.

According to EN ISO 12100-1:2003, in which this concept is strongly emphasized, the designer can consider that he has achieved an adequate risk reduction when and only when:

| > |

all operating conditions and all intervention procedures have been taken into account in the risk reduction approach ;

|

| > |

the 3-step method (see above) has been applied ;

|

| > |

hazards have been eliminated or risks from all identified hazards have been reduced to the lowest practicable level ;

|

| > |

the measures taken do not generate new hazards ;

|

| > |

the users are sufficiently informed and warned about the residual risks ;

|

| > |

the operator's working conditions and the usability of the machine are not jeopardized by the protective measures taken ;

|

| > |

the protective measures taken are compatible with each other ;

|

| > |

sufficient consideration has been given to the consequences that can arise from the use of a machine designed for professional / industrial use when it is used in a non-professional / non-industrial context ;

|

| > |

the measures taken do not excessively reduce the ability of the machine to perform its function.

|

3. The complementary roles of designer and user

Only the optimal combination of measures taken by the designer and the user ensures the achievement of the adequate risk reduction. This aspect clearly emerges if we re-examine the principles underpinning the European regulations and standards on safe machinery design:

Safety must be integrated to the greatest extent possible at the design stage, i.e., the designer must eliminate or reduce as far as possible the risk resulting from every hazard generated by the machine.

The drawing up of information for use is an inherent part of machinery design. Where a risk cannot be removed outright – by eliminating the hazard that generates it or completely eliminating the possibility of exposure to that hazard (inherent design measures) - the protective measures required must be chosen bearing in mind that safeguarding measures designed with the machine as a whole and applied when it is manufactured should always be preferred to individual protective measures.

This means that the designer cannot replace a technically feasible safety integration measure with a preventive measure which is to be taken by the user and is described as such in the information for use.

That rules out, in particular, any “agreed” sharing of responsibilities for the protection of persons between designer and user (e.g., not fitting a machine with a protective device when it could be fitted, and recommending in the information for use that personal protective equipment be worn). These reflections are condensed in the following schematic representation, which display the risk assessment / reduction process according to EN ISO 12100:2003:

Implementation of the Machinery Directive in each Member State

It is important to understand that the Machinery Directive requires each Member State to introduce national laws/regulations that implement the requirements of the Machinery Directive. It is these national laws/regulations that apply in each Member State and not the Machinery Directive. However, because these national laws/regulations differ in structure to suit individual legal systems, it is useful to have knowledge of the Directive as well because this is the source document.

Relationship with the Essential Health-and-Safety Requirements (EHSRs) of other New Approach Directives

The Machinery Directive requires that, where an identified hazard/risk is specifically dealt with by another directive, the requirements of that specific directive are the way to meet the ESHRs of the Machinery Directive. For example, if there is a hazard/risk associated with an explosive atmosphere, it is likely that the Directive 94/9/EC on Equipment and Protective Systems Intended for Use in Potentially Explosive Atmospheres (know as the ATEX Directive) will apply for those risks. Therefore, it is essential that, for a given machine, the list of identified hazards/risks is checked against the list of New Approach Directives to see if this requirement applies. The same approach must be used when writing any Harmonised Standard (see the section on EN 414 for more information).

Relationship with other Directives

Because machines are so universal, they may also be covered by directives that deal with other aspects such as the environment, particularly noise. In many, cases this requires the designer to comply with technical requirements such as noise emission limits before the EC mark can be applied.

In addition some Directives dealing with protection at work require precise technical requirements e.g. roll over protection on some vehicles and the designer must comply with these before the machine is put into use.

ETUI-REHS monitoring the revision process

Since its creation, the ETUI-REHS has been engaged in debate as to whether the Machinery Directive is genuinely achieving uniform levels of protection for workers across the entire European Union.

In 1995 a group of independent experts (the Molitor group) was asked to assess the impact of Community and national legislation on competitiveness and employment. Six years later, using the Molitor Report as its starting point, the Commission elaborated a proposal for a Directive on machinery amending Directive 95/16/EC. The main objective was to improve the various concepts referred to in the Directive and to clarify procedures for conformity assessment and market surveillance. Directive 2006/42/EC was published on 9 June 2006, after a six-year revision process that demonstrated the difficulties of striking a balance between market requirements and protecting machinery operators' health and safety. Ever since the unsuccessful attempt to completely overhaul the Directive in 1997 and throughout the process started in 2001 with the initial Commission proposal, ETUI-REHS has been participating in the debate around essential issues with OHS relevance and implications.

A selection of trade union concerns (on market surveillance, unfinished equipment, the reluctance of Member States to exchange information on unsafe equipment and the need to strengthen ergonomic dimension essential requirements, among others) has been published in a series of articles in the HESA Newsletter.

Whenever appropriate, the ETUI-REHS has also forwarded to senior EU officials its remarks and recommendations on how to improve the Machinery Directive. In 1999, when the Commission was consulting the tripartite Luxembourg Advisory Committee on its proposal, the ETUI-REHS wrote to the DG Enterprise official responsible for machinery. focusing on the scope of the Machinery Directive, the conformity procedure, market surveillance, the role of the harmonised standards, and the inclusion of foreseeable abnormal conditions in Annex I. In 2002, after the first reading of the European Parliament, the ETUI-REHS wrote to the Head of the Unit in charge of revising the Directive, transmitting some suggestions arising from the Seminar on the application of the Machinery Directive held at ETUI-REHS on 13-14 June 2002. In 2004, during the Council activity following the Commission’s modified legislative proposal, the ETUI-REHS wrote to the President of the European Council stressing the need to make the Directive more comprehensible, to clarify the duties and responsibilities of the different actors, to revise the machinery safeguard clause, and to improve the flow of information between machinery manufacturers and users, among other points.

|

| |

|

|

|

-

-

-

-

-

The revised Machinery Directive 2006/42/EC

Text of the revised Directive, Official Journal of the European Union, L 157, 9.6.2006

-

The Machinery Directive 98/37/EC

Text of the Directive, Official Journal of the European Union, L 207, 23.7.98

-

-

Action plan for European standardization

European Commission. DG Enterprise and Industry, 2007

-

EnginEurope

Report and Recommendations to the European Commission of the EnginEurope High-Level Discussion Groups, 2007

-

Mutual recognition

European Commission, DG Enterprise and Industry website

-

The New Internal Market Package for Goods

European Commission, DG Enterprise and Industry website

-

The objectives of the revision of the machinery directive

Presentation of Martin Eifel at the Workshop: "The new machinery directive - Consolidating the Internal Market for Machinery", 29th May 2007

-

The role of Directive 98/37/EC in the Single Market

Presentation of Martin Eifel at the Workshop "Welcome to the Single Market", 22 April 2004

|

| |

|

|

|

- Institut national de recherche et de sécurité

(INRS - France)

- Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform

(BERR - UK)

- Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail

(IRSST - Canada)

- Australian Safety and Compensation Council

(ASCC - Australia)

|

| |

|

|

|

- CEN

- CENELEC

- European Commission > DG Enterprise & Industry

- New Approach and European standardisation website

- Commission for Occupational Health and Safety and Standardization (KAN - Germany)

Contact person:

|

| |

|

|